Frustrated With The Food Police?

What’s your view on government attempts to regulate the food supply to make Americans more healthy? Obviously, the government needs to make sure our food is free of pathogens and toxins, but how far should this regulation go?

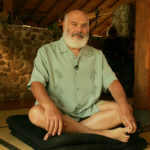

Andrew Weil, M.D. | December 5, 2013

“Food police” is a derogatory term coined by those who oppose what they view as “nanny state” efforts to tell regulate our consumption of legal foods. Attempts to rein in some of the worst excesses of the modern American diet have been slammed by those who see proposed regulations – like New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s unsuccessful effort to limit the size of sodas sold in the city – as assaults on freedom rather than a resolve to improve public health.

I think critics of the “food police” are on the wrong side of this issue. The concern of the much-maligned “food police” is the effect on health – and ultimately the cost to individuals, families and society – of choosing to eat poor diets. As my friend Marion Nestle, M.P.H., Ph.D., author and professor in the department of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, put it in her March 10, 2013 food blog: “…I can’t tell whether the opposition (to Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal) comes from genuine concern about limits on personal choice or because soda companies have spent millions of dollars to protect their interests and gin up histrionic, misinformed opposition.”

That said, some of the criticism of the food police is justified. While well-paid food writers and chefs have the resources, the know-how and the time to produce healthy meals at leisure in well-equipped kitchens, many people have far too many demands on their time, energy and financial resources to pull off similar meals on a regular basis. I urge people to choose organic fruits and vegetables and meat and poultry from organically raised animals when shopping for food, but I recognize that these products are generally more expensive that conventionally produced food and may be out of the reach of some consumers. However, I do urge those who think they cannot afford organic foods to consider the cost per pound of other types of food before rejecting organic foods as too expensive. For example, the cost of organic blueberries may be quite reasonable when compared to the cost per pound of some snack foods and some prepared foods.

If nothing else, the food police have drawn public attention to the poor quality of the standard American diet and the need to improve it. As Dr. Nestle said on her blog “we need a series of serious changes to make the healthy choice the easy choice.” What won’t be easy is taking on the powerful forces arrayed against those changes.

The upside of dietary change would be a healthier population. The downside is unthinkable.

Andrew Weil, M.D.