Anemia

What is anemia?

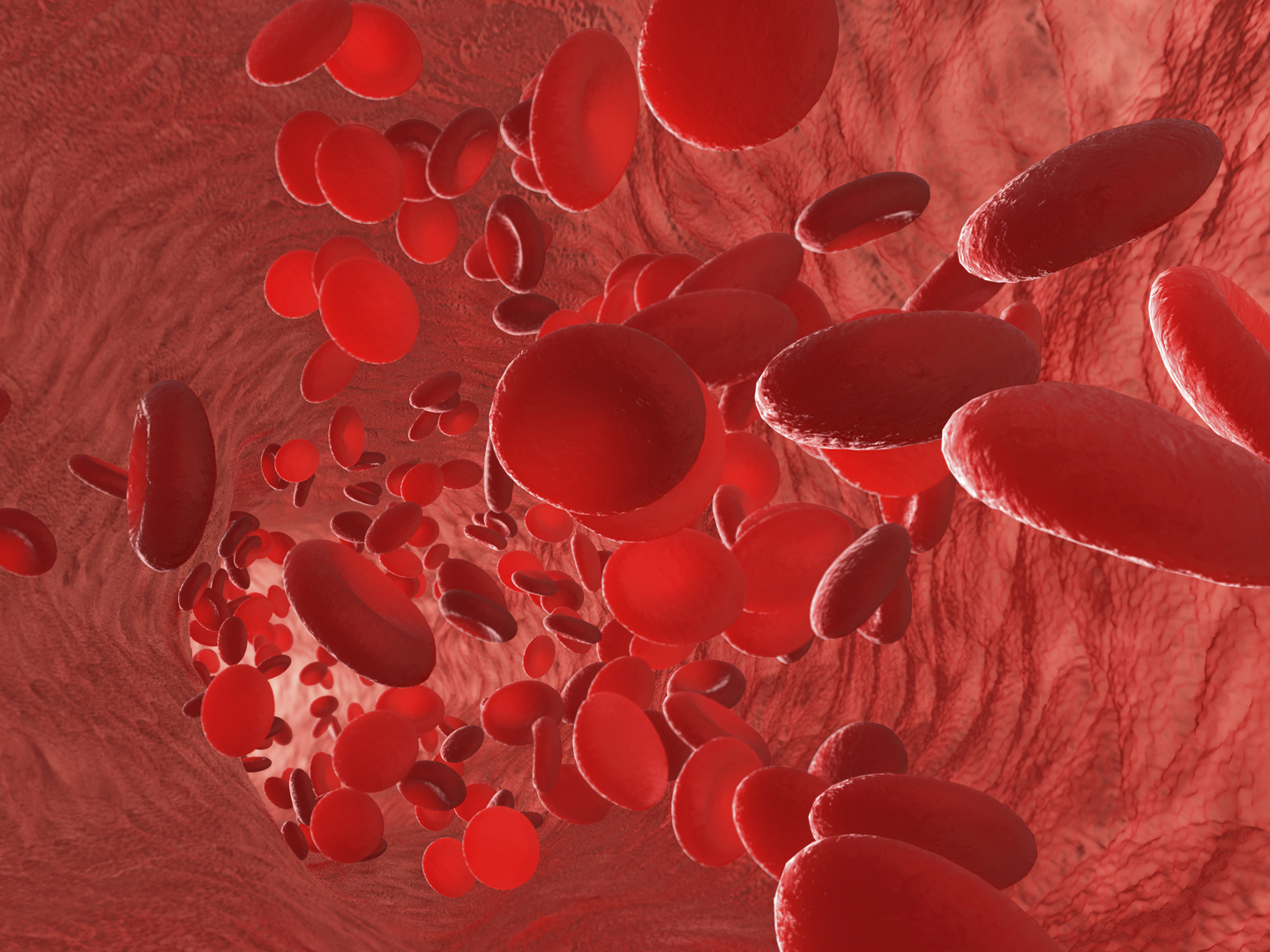

Anemia is a medical diagnosis in which a person’s blood contains a lower than normal number of red blood cells (RBCs), the cells responsible for cycling oxygen and carbon dioxide between the tissues of the body and the lungs. The symptoms of anemia can also occur if the RBCs present in the blood don’t have enough hemoglobin, a protein that allows the cells to transport oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body and that gives blood its red color.

What are the symptoms?

People with anemia typically feel tired and weak. In addition, they may experience symptoms such as:

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness

- Chest or abdominal pain

- Headaches

- Cold or numb hands and/or feet

- Low body temperature

- Pale skin

- Irritability

- Black, tarry, or bloody stools (from blood loss)

- Weight loss

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia)

These symptoms occur because the tissues in organs throughout the body may not be getting an optimal supply of oxygen, and because the heart must pump harder to cycle and deliver as much of the available oxygen-rich blood as possible.

What are the causes?

There are several different classifications of anemia, depending on the cause and the characteristics that are seen when examining the RBC’s under a microscope. RBCs are made continuously in the bone marrow and normally have a 120-day lifespan in the bloodstream. Anything that accelerates their loss or slows their production can result in anemia.

- Blood loss: This is the most common cause of anemia, and occurs when a person loses a significant amount of RBCs through bleeding. Blood loss can be caused by heavy menstrual periods, surgery, traumatic injury, cancer, and bleeding in the digestive or urinary tract.

- Low RBC production: The body requires certain nutrients to produce RBCs, including iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12. If a person doesn’t get enough of these nutrients, insufficient numbers of new cells are produced and anemia can result. Chronic kidney disease, cancer, infections, radiation therapy, some medications, and even pregnancy can also suppress the normal activities of the bone marrow and decrease RBC production.

- High RBC destruction: Some inherited blood disorders can destroy RBCs at a rate faster than the body can replace them. These conditions include sickle-cell anemia and thalassemia.

Who is likely to develop anemia?

Anemia is considered widespread and affects an estimated three million Americans. It is most common in women, primarily because of menstrual blood loss and pregnancy; older adults, who are more likely to have nutritional deficiencies or chronic conditions that cause anemia; and children younger than age two. Risk factors for anemia include:

- Diets low in iron, folic acid, and/or vitamin B12

- Blood loss

- Chronic infections

- Conditions such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver or kidney disease

- Family history of inherited anemia

How is anemia diagnosed?

A doctor can diagnose anemia by performing a physical examination, asking questions about the patient’s symptoms and medical and family history, and performing a variety of blood tests. These tests may check the size and number of RBCs, hemoglobin, and level of iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12. The doctor may also conduct further tests to identify sources of bleeding or diagnose chronic illnesses that can cause anemia.

What is the conventional treatment?

The goal of treatment is two-fold. The first objective is to increase the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen throughout the body, which is done by increasing the number of RBCs and hemoglobin to normal levels. The second goal is to diagnose and treat the underlying cause of anemia, if possible. The source of any suspected blood loss should always be determined before initiating therapy.

The conventional therapies used to treat anemia depends on the condition’s cause, severity, and nature, and can include:

- Supplemental iron to correct deficiency

- Supplemental folic acid and vitamin B12 to correct deficiency

- Antibiotics to treat infections

- Erythropoietin (Procrit) to increase RBC production in people with kidney disease

- Hormonal treatments to decrease heavy menstrual bleeding

- Blood transfusions

- Removal of the spleen to slow RBC destruction

What therapies does Dr. Weil recommend for anemia?

It’s vital to recognize that nutritional advice on iron has changed. As recently as the 1970s, the conventional wisdom was that iron is a tonic, and should be taken by virtually everyone to counteract fatigue and “tired blood.”

But more recent research suggests caution. Iron is a strong oxidant and can potentially promote the development of inflammatory conditions, including heart disease. Iron is also one of the few minerals that the body cannot readily eliminate, and overconsumption can make it accumulate to toxic levels. This is especially true of people with an inherited disease called hemochromatosis, or iron overload disease, which is believed to affect as many as one million Americans. So unless you are a menstruating woman, have had significant blood loss, or have otherwise been determined by a physician to be an appropriate candidate for iron supplementation, you should not take any supplement containing iron or otherwise take extraordinary steps to boost your iron intake. If supplemental iron is advised by a physician, you can take an over-the-counter iron supplement. Dr. Weil recommends a highly absorbable form of iron known as iron gluconate.

With that in mind, Dr. Weil suggests the following strategies for addressing mild to moderate cases of iron-deficiency anemia. These should be considered in addition to conventional therapy that addresses the root cause of anemia:

- Cook in cast-iron pots (the cooked food absorbs iron).

- Increase intake of red meat (preferably organic), chicken and fish, all of which provide some iron. Vegetarian sources include whole grains, dried beans, molasses, dried apricots and prunes, and leafy green vegetables such as kale, beet greens and chard, as well as exotic greens such as dandelions, lamb’s quarters, nettles and yellow dock.

- Eat more foods that enhance iron absorption. These include fruits and vegetables high in vitamin C, or yogurt or sauerkraut, both of which contain lactic acid, which promotes iron absorption. Fermented soy foods can aid absorption as well.

- Avoid caffeinated beverages, eggs, milk and bran, all of which can interfere with iron absorption.